“Once the full complexity of investment risks, longevity risks and Canada’s morass of taxes, credits and income-tested benefits for seniors was taken into account, this research concluded that simple, single-scenario projections of the value of a drawdown strategy are unreliable and misleading.”

– Doug Chandler, author of FP Canada’s “Retirement Drawdown Choices”

Introduction

Non-registered accounts, TFSAs, RRSP/RRIFs and their locked-in counterparts (LIRA/LIFs) each have unique tax features. Canadians who have multiple types of accounts must decide how to draw them down during retirement. The most common question we are asked is: should I draw down my RRIF/RRSP faster than required?

Your drawdown decision is potentially important because it will impact the taxes you pay and how much is left to spend. Your choice will also affect the legacy you leave to your loved ones. You shouldn’t feel inadequate if you don’t know the answer because it’s a complex problem.

Many of the common heuristics used by advisors and accountants are based on incomplete analysis stemming from an unclear objective. Furthermore, recommendations to de-register RRIFs early are usually made by analyzing a single scenario, which fails to consider sources of variability such as inflation, investment returns, and longevity.

Those who want a more thorough understanding of the decision complexities might enjoy FP Canada’s research paper: Retirement Drawdown Choices.

The minimum RRIF withdrawal rules often result in a “tax valley”

RRSPs must be converted to RRIFs by age 71 with withdrawals starting the following year. Many people who follow the minimum RRIF withdrawal rules will experience a “tax valley” between when they retire and age 72.

To illustrate, I have prepared financial projections for a hypothetical client named Mary. Mary is a wealthy 50-year-old woman with $750,000 in non-registered assets, a $1.1 million RRSP account, and a $150,000 TFSA. Mary plans to work until age 60, earning $300,000 per year, assumed to grow with inflation. Finally, Mary wishes to spend $100,000 per year during retirement, also assumed to increase with inflation. The projections assume she receives an average return on her investments of 5.4%.

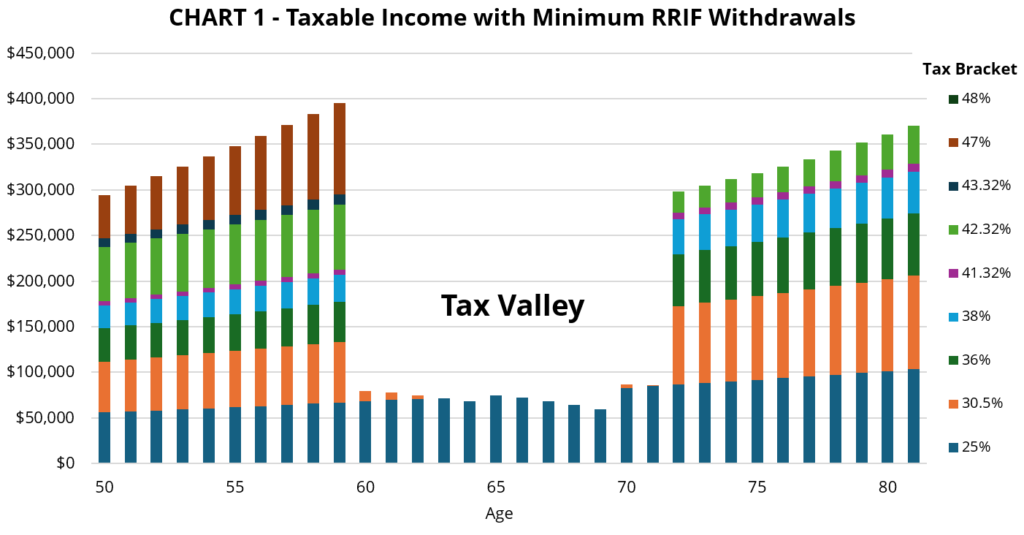

If Mary converts her RRSP to a RRIF at age 71 and takes the minimum payments starting at age 72, her taxable income will have a “tax valley” pattern, as shown in Chart 1.

- Age 50 to 59 – A high tax period due to employment income and taxable income generated from her non-registered account

- Age 60 to 71 – A low tax period because Mary’s only source of income is the growth of her non-registered account, plus CPP/OAS starting at age 70

- After age 71 – A high tax period due to mandatory RRIF withdrawals

The bar colours in Chart 1 correspond to combined Alberta/Federal tax brackets, of which there are nine, although Mary’s income only takes her through the first eight.

Source: QV Investors

Canada’s progressive tax system suggests that accelerating RRIF withdrawals might be an effective strategy to reduce taxes

In her final years of employment, Mary’s marginal tax rate is 47%. In early retirement, Mary’s marginal tax rate drops to a low of 25% because her only sources of income are modest CPP/OAS payments plus growth in her non-registered account. But at age 72, when her mandatory RRIF payments begin, Mary’s marginal tax rate increases to 42.32%.

Canada’s progressive tax rates suggest that Mary could save taxes by distributing her income more evenly throughout retirement. Voluntary RRIF withdrawals between ages 60 and 71 would increase taxable income during a period of low tax rates. By drawing down her RRIF early, taxable income will be lower starting at age 72, when tax rates are much higher.

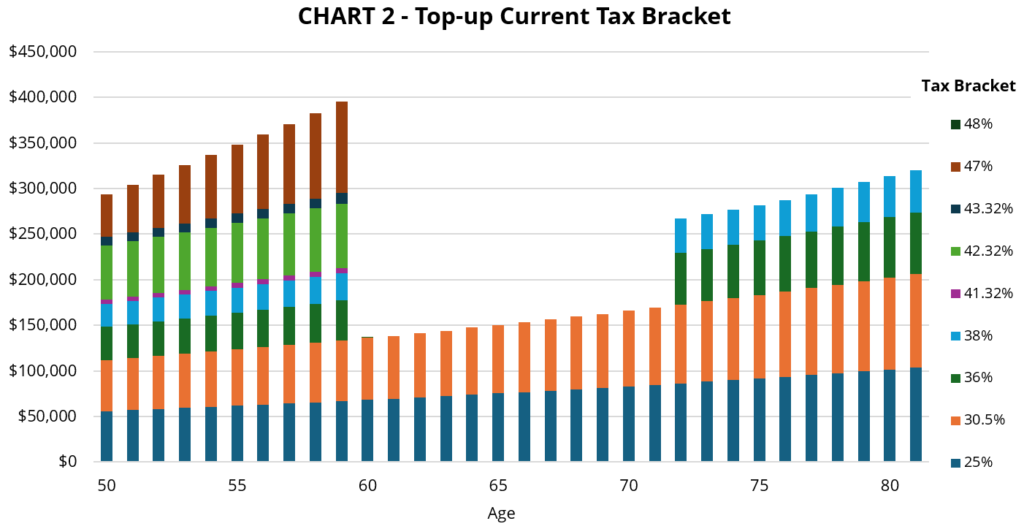

Financial planners often use a simple rule of thumb called “topping up the tax bracket.” This strategy involves withdrawing just enough money from the RRIF to reach the upper limit of the current tax bracket, without crossing into the next higher bracket. The result is the pattern of taxable income in Chart 2. As you can see, this approach reduces Mary’s marginal tax rates after age 71 from 42.32% down to 38%.

Source: QV Investors

However, by accelerating her RRIF withdrawals, less will be invested in Mary’s RRIF, and more will be invested in her non-registered account, where growth is taxed. Unfortunately, the “top-up” heuristic fails to account for this ongoing tax drag.

Following her advisor’s guidance would cost Mary’s estate $211,000 in this scenario because the tax-free compounding available in her RRIF is more valuable than the tax-bracket advantage of accelerated RRIF withdrawals.

Specifying the correct objective function

The problem is that Mary’s objective wasn’t clearly specified and therefore the analysis was flawed. In Mary’s case the optimal objective is to maximize her after-tax estate value – a cumulative measure of residual wealth – whereas her advisor used an arbitrary rule applied year-by-year without considering the cumulative effect.

It’s possible that, in some cases, the top-up heuristic may be superior to the minimum RRIF approach, but evidence is needed to support that conclusion.

Single scenarios often overstate the value of accelerating RRIF payments

Where single-scenario projections demonstrate that the “top-up” heuristic is superior to minimum drawdowns, the advantage might not exist in many other scenarios. Using average returns in each year of a projection can conceal the complexity of the issue.

For instance, if investment returns are much higher than assumed, tax-free compounding inside a RRIF is even more valuable than the tax-bracket effect, even considering the very high taxes on the RRIF account in the year of death.

On the other hand, if investment returns are significantly lower than assumed, the high tax rates later in retirement might never materialize, making it effective to give up the RRIF tax shelter today in anticipation of high tax rates in the future.

Getting advice

We explored a common drawdown rule for a single woman and demonstrated that the “topping-up” heuristic might not be effective. The situation is even more complex for married couples due to the higher tax rates that often apply to the surviving spouse and the benefits of income splitting while both spouses are alive.

To explore your situation, you and your advisor must first start by specifying the appropriate objective function. If your wealth is modest, your primary interest might be to maximize sustainable spending and minimize the chance of running out of money. Wealthier people, like Mary, are more likely interested in maximizing their after-tax estate value.

The drawdown decision is impossible to answer without preparing financial projections in a variety of scenarios. The software used by your advisor must include the complexities of the Canadian retirement and tax systems. Even then, it might be difficult to arrive at a very clear decision.

The RRSP/RRIF account types are valuable tax shelters that you’ve built up over decades. While it may possibly be the right thing to do, you should seek very convincing evidence that voluntarily paying more tax now by accelerating RRIF withdrawals is good for your long-term well-being.